So I have arrived in Latvia, and today I made my first trip to the Latvian State Historical Archives.

And I may have already found something!

Since it takes them a few days to find and bring out the requested documents, for the most part today was just filling out the forms to request the items I wanted to look at.

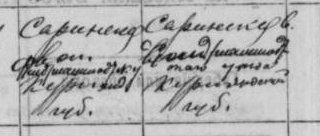

But they also have a computerized database of their pre-1944 passport holdings for people dwelling in RÄ«ga – that is searchable by name. The information the database provides is just first name, surname, father’s name and usually birthdate/place and place of registration, but the full passport file should provide more.

Using this database, I believe I have tracked down my mysterious Celmiņš ancestors – the family whose name I bear, but about whom I know relatively little about.

The great-grandparents I believe I located are Pēteris Celmiņš and his wife Anna (maiden name Liepa). The birthdates listed in the database are a couple of days off from the birthdates I have from their gravestones (one day for Anna and twelve days for Pēteris), but they are the correct month and year. No other people with the same names came close in terms of birthdates, and these were the only Anna Celmiņa (born Liepa) and Pēteris Celmiņš that were registered in the same district as each other, so chances are these are the right people.

I have requested the passport files, and these should include photos – I have a photograph of them, so this should help confirm that I have the right people. It is also possible there was a transcription mistake and the passport file will show the birthdates corresponding to what I have. Sometimes these passport files also include things like marriage certificates, so something like that to further confirm this to be the right couple would be wonderful!

If this is the right couple, my research will take me out of RÄ«ga records, and once again into the north of Vidzeme – a region that is already the place of origin for the families of two of my great-grandfathers.

Friday I go back to the archives!