Photograph of what is probably a school play or skit of some kind at the primary school in Krustpils, c. 1925. My grandmother is the girl in the middle of the first row.

It’s been six months since I posted one of these lists… well, better late than never! The summer was very busy, and I moved, and only now have I recovered where I put these papers.

Onto the names! As before, these come from a list published in 1822 by the governing authorities in Latvia, encouraging the choice of Latvian surnames, as opposed to German or Polish or Russian ones. These follow earlier posts of Government Approved, Part 1, Government Approved, Part 2 and Government Approved, Part 3.

This week’s category: Names from Objects and Things. As before, if you don’t see your exact name here, don’t panic – the authorities did not recommend diminutive forms, but most often people disregarded that and went with them anyway. So if your surname looks like a name on this list, but ends in -iņš or -Ä«tis instead, it will have that same origin. Also as before, modern renditions in brackets. If I am not familiar with a name, I’ve made my best guess as to how it would be rendered in modern spelling. If there is no change, I have not put a name in brackets.

| Ahkis (Āķis) | Airis | Ambults | Arkls |

| Atbalsts | Atspaids | Auglis | Auseklis |

| Austriņsch (Austriņš) | Awots (Avots) | Baļķis | Balsens |

| Bars | Behniņsch (Bēniņš) | Besmers (Bezmērs) | Birkaws (Birkavs) |

| Blohdis (Bļodis) | Bluķķis (Bluķis) | Bohmis (Bomis) | Bunduls |

| Dahlers (DÄlers) | Dahrs (DÄrzs) | Dakschis (DakÅ¡is) | Dakstiņsch (Dakstiņš) |

| Dambis | Deglis | Dibbens (Dibens) | Dihglis (DÄ«glis) |

| Dohbens (Dobens) | Draudeklis | Dsellons (Dzelonis) | Dselskalns (Dzelzkalns) |

| Dsirkstels (Dzirkstele) | Durwis (Durvis) | Eemaukts (Iemaukts) | Ehwels (Ä’vels) |

| Elkons (Elkonis) | Enkurs | Gabbans (Gabans) | Galds |

| Gals | Garrohsis (Garozs) | Gehrbs (Ģērbs) | Gredsens (Gredzens) |

| Grihsts (Griests) | Ihlens (Īlens) | Iskapts (Izkapts) | Jummis (Jumis) |

| Kabats | Kahts (KÄts) | Kakls | Kalts |

| Kammans (Kamanas) | Kammesis (Kamiesis) | Kammolsch (Kamols) | Karrohgs (Karogs) |

| Karrohte (Karote) | Kaschoks (Kažoks) | Katls | Kauls |

| Kausis | Keegels (Ķieģelis) | Klehpis (Klēpis) | Klehts (Klēts) |

| Knohpis (Knopis) | Kohklis (Koklis) | Kohks (Koks) | Krahsnis (KrÄsns) |

| Krampis | Krasts | Krehsls (Krēsls) | Krettuls (Kretuls) |

| KrohÄ·is (KroÄ·is) | Kuhkuls (Kukuls) | Kummoss (Kumoss) | Kurwis (Kurvis) |

| Kuschķis (Kušķis) | Laidars | Lauks | Lauschnis (Laušnis) |

| Leddus (Ledus) | Leeschkers (Liešķeris) | Lemmesis (Lemesis) | Lezeklis (Leceklis) |

| Lihgotnis (LÄ«gotnis) | Lohgs (Logs) | Lohks (Loks) | Lohzeklis (Loceklis) |

| Luhks (LÅ«ks) | Lukturs | Maiss | Maks |

| Makschkeris (Makšķeris) | Meeseris (Mieseris) | Meets (Miets) | Mehrs (Mērs) |

| Mehtels (Mētels) | Mesch (Mežs) | Muhris (Mūris) | Nams |

| Nasis | Niedris | Pagalms | Pagrabs |

| Pahlis (PÄlis) | Pakuls (Pakulas) | Pamats | Pameslis (Pamesls) |

| Papihrs (PapÄ«rs) | Paspahrnis (PaspÄrnis) | Pawehnis (PavÄ“nis) | Pellus (PÄ“lis) |

| Pihlars (PÄ«lÄrs) | Pihtnis (PÄ«tnis) | Pils | Plauksts |

| Plazzis (PlÄcis) | Plezzis (Plecs) | Pohds (Pods) | Prahmis (PrÄmis) |

| Puhrs (PÅ«rs) | Pulks | Pulkstens | Pumpurs |

| Rags | Raksts | Rats | Rausis |

| Reschģis (Režģis) | Rihks (Rīks) | Rihtenis (Ritenis) | Rinķis (Riņķis) |

| Rittens (Ritenis) | Rohbs (Robs) | Rohzis (Rocis) | Rullis |

| Sahbaks (ZÄbaks) | Sakne | Sakts | Salms |

| Sars | SchÄ·eets (Å Ä·iets) | Schkede (Å Ä·Ä“de) | Schkeps (Å Ä·eps) |

| Schkirsts (Šķirsts) | Schkuhnis (Šķūnis) | Schnoris (Šņoris) | Schohgs (Žogs) |

| Seddels (SÄ“dels) | Seeds (Zieds) | Seegelis (ZÄ“Ä£elis) | Seeks (SÄ«ks) |

| Seemels (Ziemelis) | Seens (Siens) | Seets (Siets) | Sehdeklis (SÄ“deklis) |

| Sehgelis (ZÄ“Ä£elis) | Sils | Sislis | Skabbargs (Skabarga) |

| Skaischķis (Skaišķis) | Skaitlis | Skurstins (Skurstens) | Sneegs (Sniegs) |

| Sohbins (Zobens) | Sohbs (Zobs) | Spahrns (SpÄrns) | Spals |

| Speegelis (Spīģelis) | Spihdeklis (Spīdeklis) | Spihkeris (Spīķeris) | Spilwens (Spilvens) |

| Spohsts (Spožs) | Stahds (StÄds) | Stenders | Stohbrs (Stobrs) |

| Stohps (Stops) | Striķķis (Striķis) | Stuhris (Stūris) | Sturmis |

| Susseklis (Suseklis) | Swahrguls (ZvÄrgulis) | Swahrpsts (SvÄrpsts) | Swammis (Svamis) |

| Swans (Zvans) | Swars (Svars) | Teegels (TÄ«Ä£elis) | Telts |

| Tihkls (TÄ«kls) | Tilts | Tinneklis (Tineklis) | Tirgus |

| Trauks | Trummetis (Trumetis) | Tscheekurs (Čiekurs) | Tschuhplis (Čūplis) |

| Urbeklis | Wadmals (Vadmala) | Wahrds (VÄrds) | Waigs (Vaigs) |

| Wainaks (Vainags) | Wakts (Vakts) | Walgs (Valgs) | Walnis (Valnis) |

| Wasks (Vasks) | Weesulis (Viesulis) | Wehjsch (Vējš) | Wehsts (Vēsts) |

| Wellens (Velēna) | Widdus (Vidus) | Wihns (Vīns) | Wilnis (Vilnis) |

| Zaurums (Caurums) | Zeems (Ciems) | Zeļsch (Ceļš) | Zehrtnis (Cērtnis) |

| Zeplis (Ceplis) | Zeppets (Cepetis) | Zimds (Cimds) | Zirwis (Cirvis) |

| Zukkurs (Cukurs) |

My grandparents Zenta Lūkina and Juris Celmiņš got married on this day in 1943. I do not have their marriage certificate yet, but I do have several other documents that attest to this date as their marriage.

I do, however, have this photograph from their wedding:

I don’t know how Zenta and Juris met, though I have some ideas. It is most likely that they met in one of two ways – either a “society” meeting of some kind (since both of their fathers were of “respectable” positions – Zenta’s father a judge and parliamentarian, Juris’ father an assistant bank director), or, alternately, they could have met during Juris’ farm work stints – RÄ«ga house books show that he went to RÄ«nuži (the farm/hamlet where Zenta’s family lived) in July of 1943. Whether he took this work before or after meeting Zenta, I don’t know.

I’m also curious as to what inspired them to get married during wartime, and at such a young age (Zenta was 20, Juris was 23 – it might not seem that young to some, but in terms of marriages in my family, this is quite young). Juris’ father had also died suddenly eight months earlier. Within the next year and a half, the couple, along with Zenta’s parents, headed West to escape from the advancing Soviet army. They spent several years in Displaced Persons camps in Germany, including Camp Noor near Eckernförde, and then immigrated to Canada. They arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on October 22, 1948, aboard the USS General WC Langfitt.

The couple had three children. Zenta died of lung cancer in 1959. Juris remarried and died of a heart attack in 2002.

Click for full image. Image courtesy of a cousin from my LÅ«kins family line.

Fishing manager JĒKABS ŠĪRS, 61 1/2 years old, born in Aloja, divorced.

Died on October 4, 1923, at 10 o’clock in the evening in RÄ«nuži.

Buried October 14, 1923 at the BaltÄs BaznÄ«cas (White Church) cemetery.

Daugavgrīva church book, 1923 deaths, #53.

JÄ“kabs Å Ä«rs was my great-great-grandfather. He was born in Aloja in northern Latvia to parents JÄnis and KristÄ«ne on May 30, 1862 (O.S.). When he came to live in the RÄ«ga area is unclear, but his daughter Lilija was born at Kalnciems in 1899. Sometime prior to this, he married KristÄ«ne Kukure, who is also allegedly from northern Latvia, but I have yet to find her birth record anywhere. They divorced in June of 1923.

At the time of JÄ“kabs’ death, he was living at RÄ«nuži, which was a place in what is now the VecmilgrÄvis part of RÄ«ga. Whether RÄ«nuži was a hamlet with a number of families or a property owned by the Å Ä«rs and LÅ«kins families, I’m not exactly certain yet, but today in that area is a RÄ«nuži street, which intersects with BaltÄsbaznÄ«cas street (White Church Street), where the Å Ä«rs and LÅ«kins families lived. The “White Church” in question is the DaugavgrÄ«va Lutheran Church, in whose cemetery JÄ“kabs was interred.

My grandfather Aleksandrs Francis was born on September 24th, 1920. The first twenty years of his life were, by all accounts, relatively normal for a middle-class Latvian youth growing up in the 20s and 30s. He attended an agricultural high school, followed by a degree in agronomy from the Jelgava Academy of Agriculture.

Then in 1940, everything changed. World War 2 had broken out, and the Soviet forces invaded Latvia when Aleks was nineteen. His father, Arvīds, an intelligence agent, was arrested by the Soviets, and subsequently executed. By the end of the war, Aleks had ended up in Denmark. He was twenty-four, and would never see his mother or sister again.

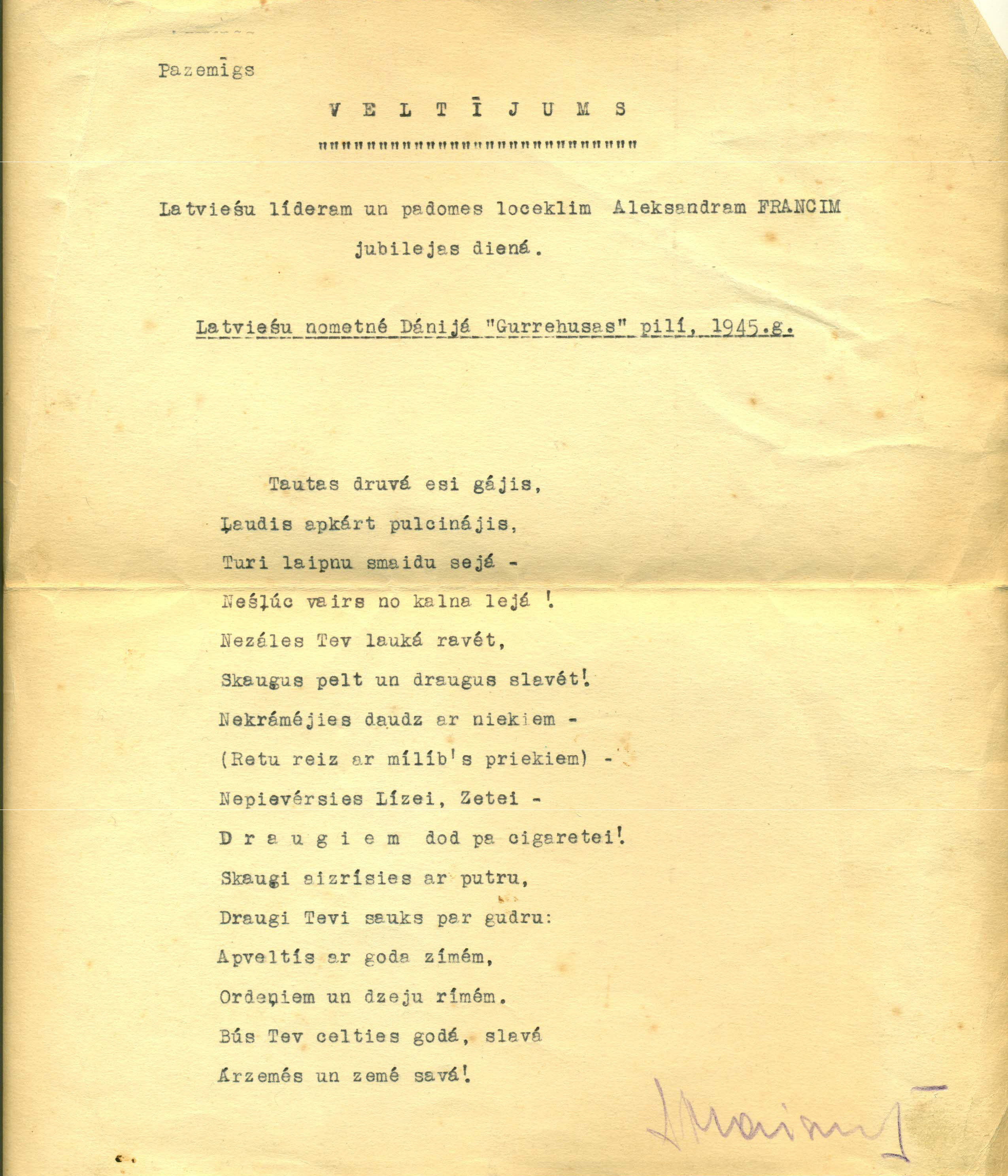

Aleks became a leader in the Latvian Displaced Persons community in Denmark, and was the Latvian representative of the Gurrehus manor DP camp. This poem was presented to him on his 25th birthday, on September 24th, 1945. Below is my literal translation – I’m sure it is littered with inside jokes and is probably partially in jest, these were probably twentysomething men writing this, after all – so it is likely that some aspects of it are lost in translation.

A humble offering

to Latvian leader and board member Aleksandrs Francis on his birthday.

Latvian camp in Denmark at “Gurrehus” castle, 1945.

(You have) Gone into the field of our people,

Gathered people all around you,

Keep a pleasant smile on your face –

Don’t slide back down the mountain!

There are weeds for you to weed in the fields,

Blame the envious and glorify friends!

Don’t worry yourself with trivial things –

(Rare is the time with love’s joys)

Don’t pay attention to Liza or Zete –

Give your friends a cigarette!

The envious will choke on porridge,

Friends will call you smart:

They’ll give you commendations,

Medals with rhyming poems.

May you rise in honour and glory,

Abroad and in your country!

While at first glance, a document like this might not appear to have genealogical value besides personal interest, looking more closely does reveal important elements – namely, dates and places. I knew about the Gurrehus DP camp from my grandmother and great-aunt (and I believe it is where my grandmother and grandfather met), and have visited the site personally, but I had thought that it was one of the later places that they stayed during those four years in Denmark. This shows that Aleks at least was already at Gurrehus in 1945, not long after the end of the war. This can help to reconstruct his post-war movements and places of residence. Once I obtain ITS documents for him, then I will be able to get a fuller picture of his life after leaving Latvia and before arriving in Canada.

This post is the first in a series that I’ll be making about events in my ancestors’ lives, on the days that the events took place.

My reasons for this series are twofold – first of all, it helps me organize my own family documents and files, which is something that has been severely lacking, especially in this past year when I’ve been so wrapped up in other activities that I’ve barely had time to touch my own family research. Secondly, it provides concrete examples to you, my readers, of the different kinds of documents that you may be able to consult in your own Latvian research.

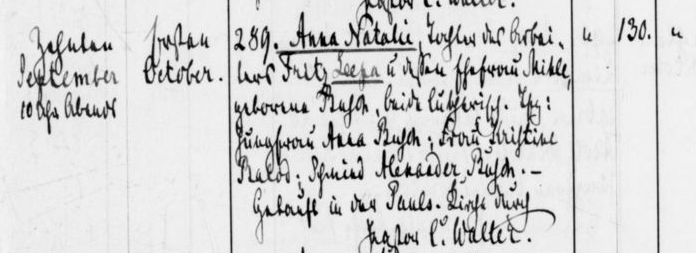

Birth: 10th of September 1895, 10pm

Baptism: 6th (?) of October 1895

No. 289 – Anna Natalie, daughter of worker Fritz Leepa and his wife Mihle born Busch. Both Lutheran. Godparents: Miss Anna Busch, Mrs Kristine Balod, smith Alexander Busch. Baptized at St Paul’s Church, Pastor C. Walter.

This may be the birth record of my great-grandmother Anna Liepa. I’ll get back to the “may be” in a bit, first a bit on her.

Anna Liepa was born in Rīga on September 22, 1895, according to the Gregorian calendar. At the time of her birth in the Russian Empire, her birthday was September 10. Her tombstone cites her date of birth as September 23, but every document of hers that I have (internal passport, marriage record, numerous house book entries, etc.) all state September 22 (and in the early years of independent Latvia, both the Gregorian and Julian dates are cited together). She was a bookkeeper, and married Pēteris Eduards Celmiņš in Rīga on September 17, 1919.

Now back to the “may be” – Anna was born in RÄ«ga, which was and is the biggest city in Latvia. This means there are lots of records to check, and both her first and last names are fairly common. I haven’t consulted all of the RÄ«ga records yet, but this one certainly is the best candidate.

My reasoning, in favour of this being her birth record:

Points against this being her birth record:

So the search continues. Is this the right record? I won’t know until I check the rest of the churches. I could also obtain her death record and hope that it has her mother’s first name and maiden name on it. Until then, Anna remains one of my problem ancestors.

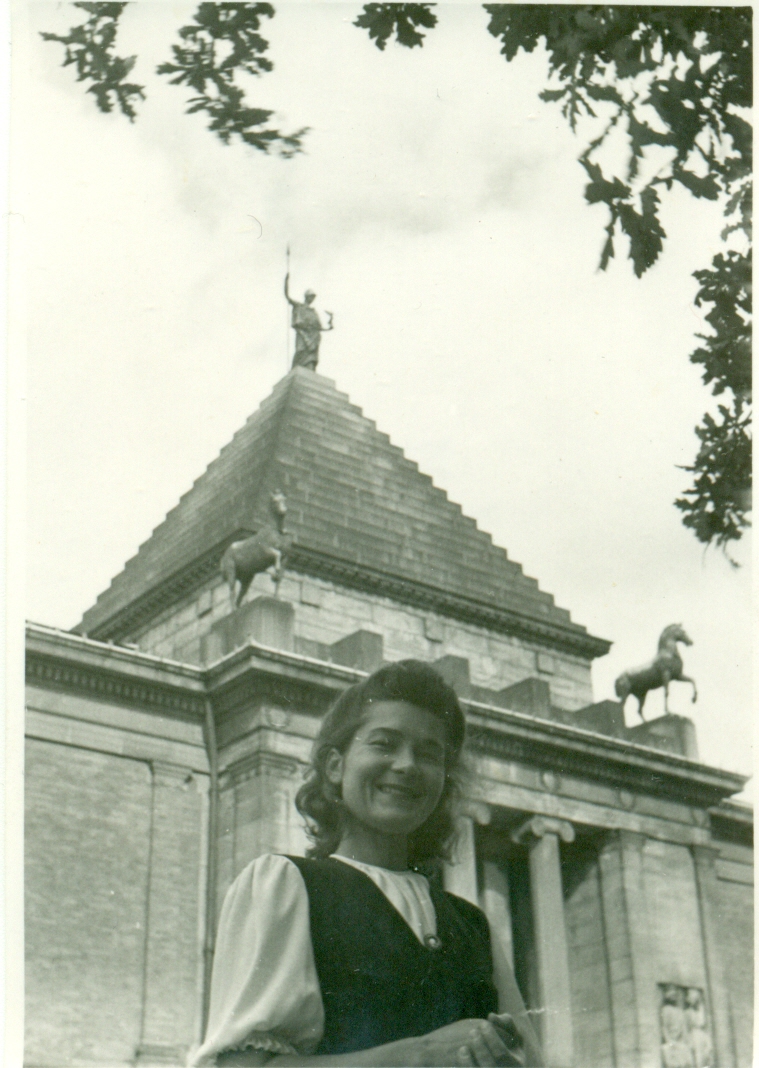

Can anyone help identify the building in this photograph? I’m pretty sure it is in Denmark, since it is a photo of my grandmother from her collection of Displaced Persons camp photographs, c. 1945-1949. However, I haven’t been able to turn up any results. Also possible that it could be in northern Germany around Hamburg or Bremen. I think I have seen this building personally, but I can’t recall where it was or what it is called. Thanks for any help!

So you want to use Raduraksti, but you’re intimidated, because you don’t know German or Russian. That’s okay! With a bit of work, you can find everything you need to know from these records, without needing to be fluent, or even proficient, in the languages. It is just a question of being able to extract the relevant information. Prior to 1891, most records will be in German, after 1891, usually in Russian, often (but not always) with Latin transliterations of names provided.

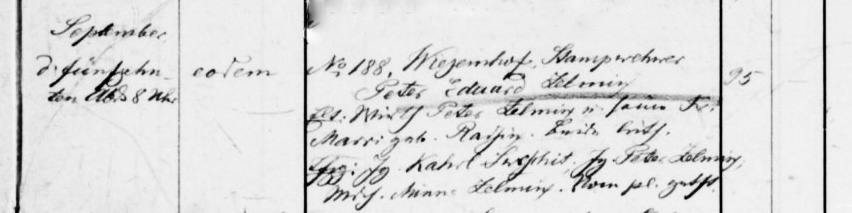

This is an image of a typical 19th century Lutheran baptism record (which serves as a birth record prior to civil registration). Records for other religions are different, and I will probably cover them later. This is the format used most often across the Latvian provinces, though there was a different format used in Kurzeme (the western province) occasionally, and I will look at that one later as well.

My great-grandfather’s birth record, TrikÄta Lutheran church, 1888.

The first two columns are pretty simple – the date of birth and the date of baptism. In this case, the date of baptism says “eodem” which means “the same” – see higher up in the column. A number of children may have been baptized on the same day, and the scribe only wanted to write the date out once.

The third column has all the important bits in it, so this is where you really need to start paying attention.

The first item will be the record number – this will be what you want to cite when you are referencing your source in your genealogical records, in addition to the year of the record. While page numbers can be useful, they can also vary – I’ve seen numerous records where there are several page numbers in the corner of the scanned sheet, as well as the page navigation numbers within Raduraksti. Any of these can be changed again, so while you should record them for ease of retrieval, the “official” reference number should be the one that doesn’t change – that of the record.

Next is the city/town name, or, more commonly for rural parishes, the name of the manorial estate and the name of the farm. In this case, it is “Wiezemhof Stampwehwer” – in Latvian, Vijciems estate, StampvÄ“veri farm. A good (though not comprehensive) list of German names and their Latvian equivalents is available here.

Then we finally have the name of the individual who was baptized – in this case, “Peter Eduard Zelmiņ” – or, in modern Latvian, “PÄ“teris Eduards Celmiņš”.

The next section will show the names of parents, with later records usually also including the mother’s maiden name (indicated by “geb.” in German or ур. in Russian) – here, “Peter Zelmiņ” (PÄ“teris Celmiņš) and “Marri geb. Radsin” (Marija née Radziņa). Before the father’s name, a record will typically list the father’s occupation as well – in this case “Wirt”, meaning landlord/land manager (either the owner of the farm, or the person in charge if the farm was still owned by the manorial estate owner). In Russian, it would be хозÑин (for men), хозÑйка (for women). Other commonly listed occupations (German/Russian) are Knecht/батрак (farmhand), Arbeiter/работник (worker), Soldat/Ñолдат (soldier) and Tischler/ÑтолÑÑ€ (carpenter).

The little notation after the parent’s names indicates their religion. In a Lutheran church record, typically this will say “both Lutheran”, but sometimes one of the other parents (usually the mother, though not always) will be of a different religion (As noted in this post, I found a random British man living in southern Latvia, whose children were baptized in the Lutheran church, while he himself was Anglican).

The following names are those of the witnesses/godparents – this section might only list the names of the people, might list their occupation or their non-married state (“Junggeselle” for “bachelor” and “Mädchen” or “Magd” for “maiden”). Sometimes they also mention where that person lives – this is how I found one of my great-great-grandfathers, by consulting the church records local to a woman with the same surname that had been listed as one of his daughters’ godparents.

… and with that, you’ve retrieved the key data! There are, of course, other notations, but these are the key features that you need to find to further your research.

What have you managed to find? What key facts about your ancestors have you learned through Raduraksti recently? Share your stories below!

RÄ«ga is the capital city of Latvia and the largest city in the Baltics. Since Latvian records are largely unindexed, this means that locating an ancestor in RÄ«ga is like looking for a needle in a haystack.

If your ancestors were ethnic Latvians, however, you might find yourself lucky – most ethnic Latvians in the capital arrived towards the end of the nineteenth century. In 1897, RÄ«ga was 45% Latvian, in 1867, only 23%. Therefore, if your ancestors are ethnic Latvians, there is a good chance that you might only need to deal with RÄ«ga records for a generation or two.

Thus the title of this post – how can you most efficiently look through that haystack of records to locate your ancestors and link them to a parish outside of RÄ«ga, and thus a place that can be searched much more easily?

1. Passports. The Latvian State Historical Archives has a collection of internal passports for RÄ«ga residents in the inter-war period. The good news is that they are indexed on a computer for ease of searching. Bad news is that they are not online, and only available by searching the database onsite. These passports note both place of residence and place of birth. Also important is “place of registration”, which can often be the place of birth – even if they haven’t lived there in years. One of my great-grandfathers was still registered as a citizen of Vijciems parish, even though at the time of issuance of the passport he had been living in RÄ«ga for at least a decade.

2. 1940 Telephone Directory. Available online at GenealogyIndexer (has all of Latvia, scroll down to find RÄ«ga). Now, not everyone had a telephone, but it is a start. This can be used to locate an address, and then you can look for parish records for that area. Of course, people move, and sometimes frequently, but a starting point is better than nothing.

3. 1897 All-Russia Census. Available on Raduraksti. The records for RÄ«ga are fairly complete, and organized by street name. The census mentions place of birth and religion, both important tools to locate the proper religious BMD documents.

4. Religious records. Available on Raduraksti. There are many religious records available for RÄ«ga, so if you’ve narrowed down where your ancestors lived, start searching in nearby parishes, and then expand your search from there. RÄ«ga records sometimes contain rudimentary indexes (still handwritten), available at the beginning or end of the book. Check both to see if one is available. If someone is a recent migrant to RÄ«ga, any information pertaining to them with regards to “home parish” will frequently reference their non-RÄ«ga parish (see above with regards to place of registration). This is most common with marriage and death records, so if you know when an ancestor died in RÄ«ga, find their death record first to see if they were born in RÄ«ga as well.

5. School records. If your ancestor went to school in RÄ«ga, there may be extant records for the school that could provide information on where the student was from. Sometimes school archive files (available at the Latvian State Historical Archives) will contain birth certificates of students, previous school transcripts, and so on.

6. Revision lists. These are available on Raduraksti. If you find your ancestors were in RÄ«ga prior to the early 1860s, you will need to head to the revision lists. Now, the ones for RÄ«ga are more complicated than for rural parishes – they are arranged by social class and, in some cases, religion (the religious groups most likely to have separate lists are Jews and Old Believers). Alphabetical indexes appear to exist for some of the lists, but not all of them. Raduraksti has many different lists relating to RÄ«ga, so you may have to sort through them for awhile to find who you’re looking for. It appears that for the most part, the latest date on these documents is 1863.

Another thing to remember is that your ancestor might not have been from RÄ«ga at all – just like emigrants from other countries, people might name the largest city to their home as their place of birth, when they were actually from the countryside. So unless you have a document (preferably of Latvian origin, since they would be most likely to be correct on Latvian places of residence and birth) that specifically links your ancestors to RÄ«ga, do not assume that is where they are from, just because it is a large population centre. This holds especially true for ethnic Latvians – while the share of ethnic Latvians in RÄ«ga did increase in the late 1800s and eventually become a majority in the interwar period, ethnic Latvians were still a predominantly rural population. If your ancestors were not ethnic Latvians, however, their chances of being RÄ«ga-born for centuries are much higher.

Have you searched for your ancestors in RÄ«ga? Do you have any other tips to share for RÄ«ga searches? Add them below!